Introduction

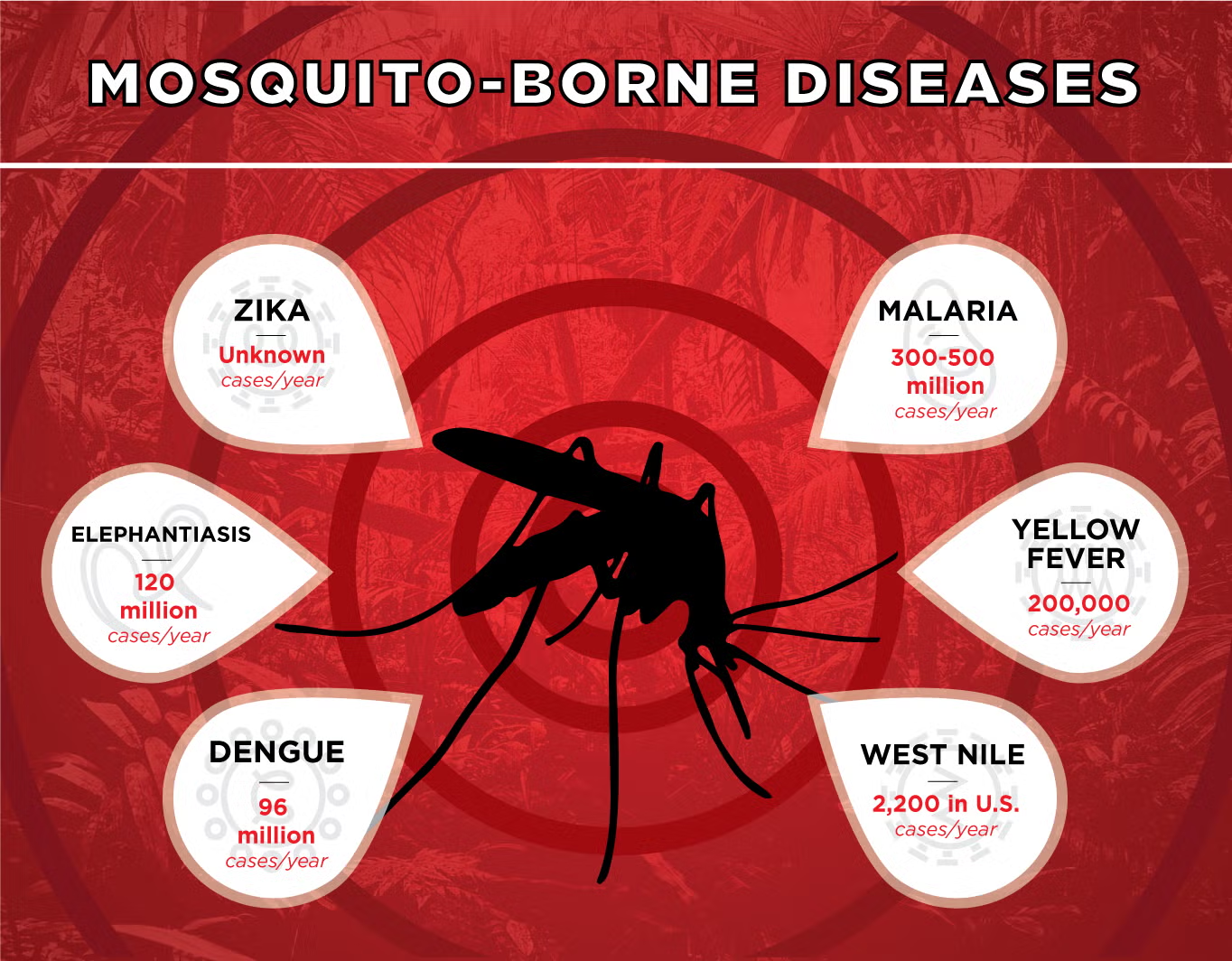

According to the CDC, the mosquito is the world’s deadliest animal, killing more people than any other animal in the world. Mosquitoes are common in many parts of the world, especially in Brazil, Indonesia, Australia, and the Philippines. They are considered vectors, meaning they spread germs and diseases to humans, which can make them very sick. Some vector-borne diseases that mosquitoes spread include, but are not limited to, West Nile virus disease, dengue, chikungunya, zika, lymphatic filariasis (LF), yellow fever, and malaria. Thus, it is of utmost importance to find a solution to prevent mosquitoes from transmitting these potentially fatal diseases.

Dengue

The first disease, dengue, also known as break bone fever, is a viral infection transmitted by mosquitoes in subtropical/tropical climates. In fact, according to the World Health Organization, recent reports show that the incidence rate of dengue went from 505,430 cases in 2000, 5.2 million cases in 2019, to a whopping 6.5 million cases in 2023. In fact, it is also the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral illness, with a “30-fold increase in global incidence over the past 50 years” (World Mosquito Program). Even so, the number of cases is significantly underreported. However, the incidence of dengue is only going to increase exponentially, especially as climate change and global warming prevail, ultimately allowing Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquito populations to increase. Additionally, one study concludes that 3.9 billion people are at risk of infection with the dengue virus. While most people with dengue have mild or no symptoms, it can still be fatal for those who do showcase symptoms. These symptoms include high fevers (reaching 104°F), pain behind the eye, nausea/vomiting, severe abdominal pain, rapid breathing, and pale and cold skin, among others. Dengue can be especially dangerous if contracted for a second time, as symptoms tend to be much more severe, or even fatal.

Zika

Another virus that spreads primarily as a result of the Aedes mosquitos is zika. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) was forced to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) as a result of the side effects of the zika virus. Similar to dengue, most people will be asymptomatic, but for some this virus can cause severe damage. Regular symptoms of zika include mild rashes, fever, conjunctivitis (commonly known as pink eye), muscle and joint pain, and headaches. However, zika is a lot more problematic for pregnant women. The PHEIC called in 2016 was partly because zika can result in congenital malformations in infants, or even stillbirth or preterm birth. In addition, infection in children and adults can also cause Guillain-Barré syndrome (a rare condition where the immune system attacks the peripheral nervous system), neuropathy (a form of nerve damage), and myelitis (the inflammation of the spinal cord).

Chikungunya

Chikungunya is a viral disease caused by the chikungunya virus (CHIKV), which is an RNA virus. According to the WHO, CHIKV outbreaks have been occurring since 1952, and have become more frequent as time goes on as the Aedes albopictus mosquitoes continue to reproduce in more and more countries. The symptoms of this viral disease include fevers, joint swelling, headache, nausea, fatigue, rash, and deliberating joint pain that can last for weeks or even months after infection. While most patients fully recover from this disease, eye, heart, and neurological complications have been reported. Moreover, infants/children and the elderly are more likely to become severely ill from this virus, thus increasing their risk of death. However, unlike dengue and zika, once an individual has recovered from this virus, they are likely to have immunity from future infections.

Yellow Fever

Yellow fever, a disease caused by arboviruses, is transmitted when the Aedes and Haemagogus mosquitoes bite humans (CDC). Out of the diseases mentioned, this is the most severe as it has a higher potential to be fatal. Yellow fever is usually characterized by its symptoms of fever, muscle pain, headache, loss of appetite, and nausea and vomiting. Similar to the other diseases mentioned, some infected with yellow fever will be asymptomatic, but it is still a very dangerous virus. This is because some patients enter a second (and very toxic) phase about 24 hours after recovering from their original symptoms. Here, high fevers return, affecting both the liver and kidneys. Jaundice develops, resulting in dark urine and abdominal pain, often accompanied by vomiting. Additionally, bleeding may occur from the mouth, nose, eyes, or stomach. About half of the patients who enter this second toxic phase of yellow fever will die within 7-10 days of these new symptoms.

What is the World Mosquito Program?

Due to the harmful nature of these diseases and their severe side effects, a solution is necessary in areas where mosquitoes are densely populated and continuously spreading these illnesses. Thus, the World Mosquito Program (WMP), a collection of non-profit companies owned by Monash University in Australia, has devised a safe and effective solution to mitigate these issues. The WMP has staff working in Oceania, Asia, Europe, and the Americas, with offices in Australia, Vietnam, France, and Panama. Furthermore, the projects they are working on (which are operating in 14 countries) have protected over 11 million people worldwide. The primary goal of the WMP is to release Wolbachia mosquitoes, which they started doing in 2011, to decrease the risk of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes transmitting viruses to humans. Specifically, the WMP is trying to limit the cases of dengue, zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever: all diseases mentioned above. After several trials, the WMP’s method of eradicating these diseases worldwide has seemed to work. Reports demonstrate that some vector-borne diseases have been eliminated locally! The WMP continues to expand its program to more countries, aiming to help more people prevent severe illness in the future.

How Are They Solving This Issue?

WMP has worked wonders for communities and has protected individuals worldwide, but how? In 1924, a tiny bacteria called Wolbachia was discovered in the reproductive systems of mosquitos by Hertig and Wolbach, according to Kenneth M Pfarr. In fact, about 50% of insect species carry this bacteria, and it survives by manipulating the reproductive system which could possibly make the cytoplasm “incompatible.” Thus, when an uninfected female mates with an infected male mosquito, they could potentially create unviable offspring. However, Wolbachia lives inside cells and is passed down through an insect’s eggs. Additionally, Wolbachia can spread rapidly due to cytoplasmic incompatibility, enabling it to invade populations quickly from the release of relatively few bacteria. While Wolbachia may be harmful to insects like mosquitoes, fruit flies, butterflies, moths, and dragonflies, it is completely safe for humans and the environment.

Mosquitos, in general, do not “naturally” carry diseases, but instead pick them up from infected people. If a mosquito bites a person infected with this disease, it can transmit the illness to the next person, which explains why these diseases spread so rapidly. As mentioned earlier, the Aedes aegypti mosquito is the primary cause of vector-borne diseases such as dengue, zika, chikungunya, yellow fever, and more. These mosquitoes originated in Africa, but due to the slave trade and world wars, they eventually spread to Asia and across the globe. Thus, the number of people affected by these viruses has exponentially increased. Luckily, while many mosquitos already carry Wolbachia, the Aedes aegypti mosquito doesn’t. The WMP found that Wolbachia prevents mosquitoes from transmitting viruses like dengue, chikungunya, and zika, as these viruses cannot grow in their bodies when Wolbachia is present. The WMP collaborates with local communities to breed Wolbachia mosquitoes and release them in areas with high levels of mosquito-borne diseases. This effort helps reduce the risk of disease as the Wolbachia mosquitoes integrate into the local mosquito population, ultimately benefiting many communities.

Conclusion

The World Mosquito Program offers an excellent solution to mitigate the number of vector-borne diseases that mosquitoes carry, and ultimately transmit to humans. Not only is their solution safe and effective, but is also self-sustaining and harmless to the ecosystem. Unlike more costly solutions that can create harm (such as using pesticides), WMP’s method doesn’t actually “suppress” the mosquito population, and doesn’t involve genetic modification. In fact in Queensland, Dr. Richard Gair, who is a director and Public Health Physician, notes that “Far-north Queensland is now essentially a dengue-free area for the first time in well over 100 years” thanks to the WMP. To learn more about the impressive work WMP is doing and how they are helping communities across the globe, visit their website here!

Average Rating